Ballet is an incredibly demanding physical artform which rivals Olympic sports like gymnastics and skating for the extremes of strength, control and flexibility required to perform ballet to a high level. The risk of injury is always present with any physical activity, and ballet is no exception. The level of risk depends on the amount of time spent training and the interaction of ballet training with other physical practices and habits formed by the dancer. Adults participate in ballet at a variety of levels from beginner to seasoned professional level, and the context within which they train, their knowledge about injury prevention and correct technical execution will influence whether and how often the dancer sustains an injury, and how quickly they recover.

The key areas of the body that are prone to injury in ballet dancers are:

Lower back:

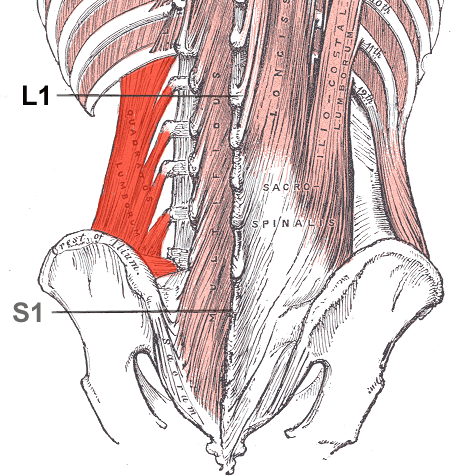

Positions like arabesque and attitude where one leg and the spine are fully extended, require the dancer to strongly engage the erector spinae, quadratus lumborum and external obliques to create back extension and rotation of the rib cage in opposition to the external rotation of the hip. The glutes are engaged to extend the hip, requiring the psoas and adductors to be stretched to their range limits. Over training or increasing intensity of training, or increasing difficulty of workouts, can put pressure on the back extensors, especially if the dancer is focussing on flexibility and specifically aiming to increase their active range of movement in back extension.

Ballet dancers train for years to increase the flexibility of the lumbar spine and engage their spine extensors, glutes and hamstrings to achieve the attitude and arabesque positions

Hip joint:

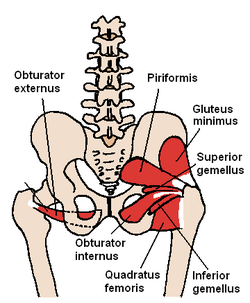

Ballet requires that the dancer train their hip joint to achieve maximum external rotation using the glutes, particularly minimus and medius, pirirformis, superior and inferior gemellus, and obdurator externus and internus. Using the hip in a fully rotated position inhibits the full power of the gluteus maximus for use in plyometric movements as ballet prioritises the aesthetic of an open hip joint over the potential power available when the large postural muscles are recruited into movement. Ballet dancers use the fully externally rotated position of the hip in 95% of movements in training, performance and competition, so it is virtually guaranteed that they will experience tightness and muscle shortening in this area. Care should be taken to fully stretch the rotator group and apply soft tissue techniques where necessary to release this area. It is not unusual for ballet dancers to experience sciatica symptoms when their external hip rotators are over used.

In addition to the rotators of the hip, the tensor fascia latae and iliotibial band, along with vastus lateralis, are recruited to both maintain control of balance when the hip is turned out, as well as extend the leg to side and back positions, so these muscles similarly are often shortened and over developed in ballet dancers. Cross training to build strength in the adductor group and vastus medialis is important to avoid problems with the knees.

The muscles of the external rotator group are engaged to achieve the signature posture of a ballet dancer, with pelvis lifted reducing the pelvic tilt and curvature of the spine, the weight carried forward in the hip joint and both hips open to allow increased range of movement

External rotation and extension of the hip and knee are essential for the majority of ballet movements and positions, leading to sometimes excessive development of the ITB, TFL and Vastus Lateralis

Knee joint

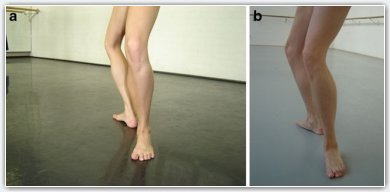

Poor technique and unbalanced training can lead to knee problems

Lack of control in the lateral rotators leads to dangerous forces through the knee when balancing weight on a bent leg

Especially in non-professional dancers who train infrequently, short psoas and weak external rotators lead to a lack of control of the hip. This in turn leads dancers to over pronate at the ankle and rotate excessively through the knee joint, running the risk of sprains, tears and injuries to the meniscus and ligaments of the knee.

Commonly poor technique leads to over-pronation “forcing turnout” “rolling” “gripping” the quads or calves. Correct technique uses the rotation of the hip joint to rotate the leg as a whole, rather than force the ankles to evert excessively.

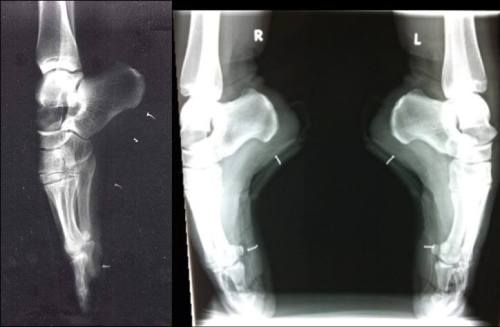

Ankle and foot

Ballet places significant emphasis on plantarflexion and extension of the forefoot and toes, including using the toes to balance the entire body weight during pointe training and performance techniques. Common injuries include peroneal, soleus and flexor hallucis longus overuse injuries, lateral ligament sprains or tears, metatarsal stress fractures particularly 4th and 5th metatarsals, “bunions” or inflammation of the large toe joint, flexor hallucis brevis strain or inflammation, plantar fasciitis and achilles sprain and rupture. Inflammation of the tibialis anterior or “shinsplints”, compartment syndrome or stress fractures of the tibia are common, particularly if the dancer is training lower leg action such as petit allegro or a lot of jumps or pointework, or if they rehearse or perform on hard or un-sprung floors or slippery surfaces without appropriate ballet specific non-slip flooring.

Dancers use full extension of the knee and plantarflexion of the foot, including lengthening the toes into the same line as the metatarsals (rather than curling them under) which is especially important when training en pointe…. which sometimes exacerbates the “bunion” on the big toe if shoes are fitted too tight

Poor technique at the ankle may require strengthening of the eversion muscles (especially peroneals) but may be due to incorrect hip alignment caused by tight hip flexors and weak hamstrings, hip rotators and abdominals.

Powerful jumps are a signature of male ballet dancer’s technique, requiring very strong legs. Women also are required to demonstrate explosive leg power and flexibility in athletic jumping maneges. Take off and landing are risky for distribution of force injuries, particularly movement involving a turn or twist of the body in the air. Achilles tendon rupture is not uncommon among elite level dancers, or dancers who have recently increased their training load or attempted a more difficult level jumping movement. A dancer’s landing technique will expose weaknesses in their external rotators and ankle stability, so once again it is important to target conditioning training to these areas to prevent injury.

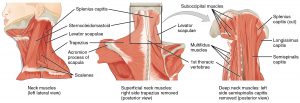

Neck and upper back

Although dancers focus on training a very mobile and flexible back and neck, they often experience pain and stiffness arising from training to hold head and arm positions for long periods and perform repetitive, fast movements, particularly head movements during pirouettes (turns). Some dancers do experience scoliosis, which may actually be helped by ballet training if the focus is on balancing the movement equally on both sides to create better symmetry and flexibility.

Flexibility and hypermobility

Dance training is generally a balanced workout which develops the muscles of the body evenly, however, problems sometimes occur when the dancer has poor posture or physical limitations arising from other activities or their individual skeletal structure and muscle development.

Most dancers are hypermobile, and train to the ends of their range in order to achieve the impressive extensions so desired in ballet performance and competition. Stretching techniques have been borrowed from rhythmic gymnastics and applied to ballet training, which can be dangerous if incorrectly performed and unsupervised. Conversely, neglecting flexibility can put ballet dancers at risk of muscle tears when they attempt to achieve end of range extensions without properly preparing their muscles to work at that range.

Factors contributing to injuries:

– Slips, trips and spills

– Overtraining or rapid increase in intensity

– Muscle imbalances and incorrect technique

– Compensating for lifestyle factors

– Compensating for non-ideal genetic body characteristic:

– Lack of flexibility

– Hypermobility

– Problems with feet and ankles

– Limited lateral hip rotation

– Scoliosis or other congenital spine or joint problems

– Inappropriate facilities for performance or training